It's all about context

There are a variety of binaries that I use daily that utilise a static 'context' so that the commands run against a specified environment. These tools have some state, most commonly a file on disk somewhere that references the context they are currently set to.

It's too easy when using tools like kubectl, helm and gcloud to inadvertently run a command against the wrong cluster or project because you have forgotten that you have switched to production. Hopefully, the command is ultimately harmless, but it could easily not be.

This post is to share how I help to mitigate the risk of accidentally running destructive commands against production infrastructure using gum, which is an awesome tool that allows developers to build powerful TUI (terminal user interface) based scripts.

Of course, an argument can be made around not having the level of privilege to do anything dangerous in production contexts in the first place, but it's like all things a trade-off between security and practicality. Having access to production clusters is necessary at some level to be able to respond to incidents and investigate issues, how this access is managed is not the topic of this post, but is in itself an interesting topic.

Visual signals

Before I get onto the meat of the post, around how I use gum to help prevent accidents, it's good to note some of the other techniques that both myself and others use to aid with this goal, because as with most things in life, more is often better.

Custom Prompts

Most shells provide a mechanism for customising the 'prompt' i.e. where user input is taken. Customisations range from showing the current status of a project in version control, how long a command took to execute, the exit code of a command and so on.

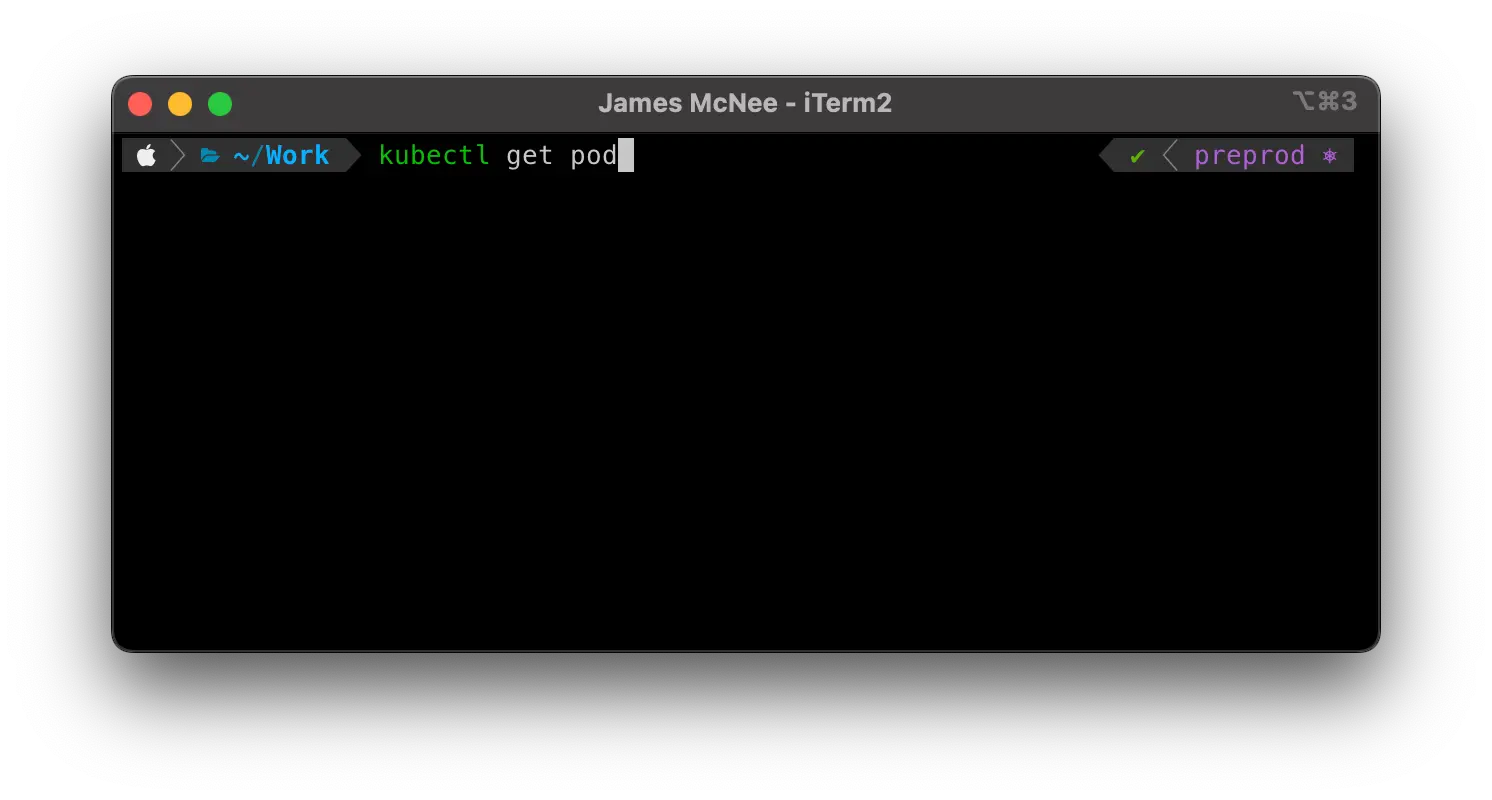

A very useful customisation that one can add to their shell is to show the current Kubernetes cluster that they are pointing at and if desired, the namespace they have active too. You can see this in practice in the above screenshot.

Colour Coded Shells

Another approach, although not one that I use, is to have the title bar of the terminal window change colour depending on the current context. Many people choose to have their shells getting more and more red as they step through environments closer to production.

Gumming it up

The above two approaches are good and do help to prevent mishaps, but they still rely on the user noticing a visual cue. What I wanted was something that would pull the emergency break for me and prevent me from slamming into the wall that is, a production incident.

What is Gum?

Gum is a binary that can be used to build powerful TUI (terminal UI) based scripts quickly and easily, check out the readme on their GitHub for some examples and how to use it.

Essentially though, gum allows you to add dynamic user input into an otherwise boring shell script, notable features are:

- Input requires the user to enter some input, this can be used inline or assigned to a variable.

- Write allows the user to provide a block of multi-line text.

- Filter and Choose will show a list of choices, the former allowing the user to type to filter. Supports multi-selection etc.

- Confirm is what we will be focusing on. This shows a prompt to the user seeking confirmation.

Creating a kubectl wrapper

I am going to focus on kubectl for the remainder of this post, but this technique can be applied to basically any binary. I use it for both kubectl and helm currently.

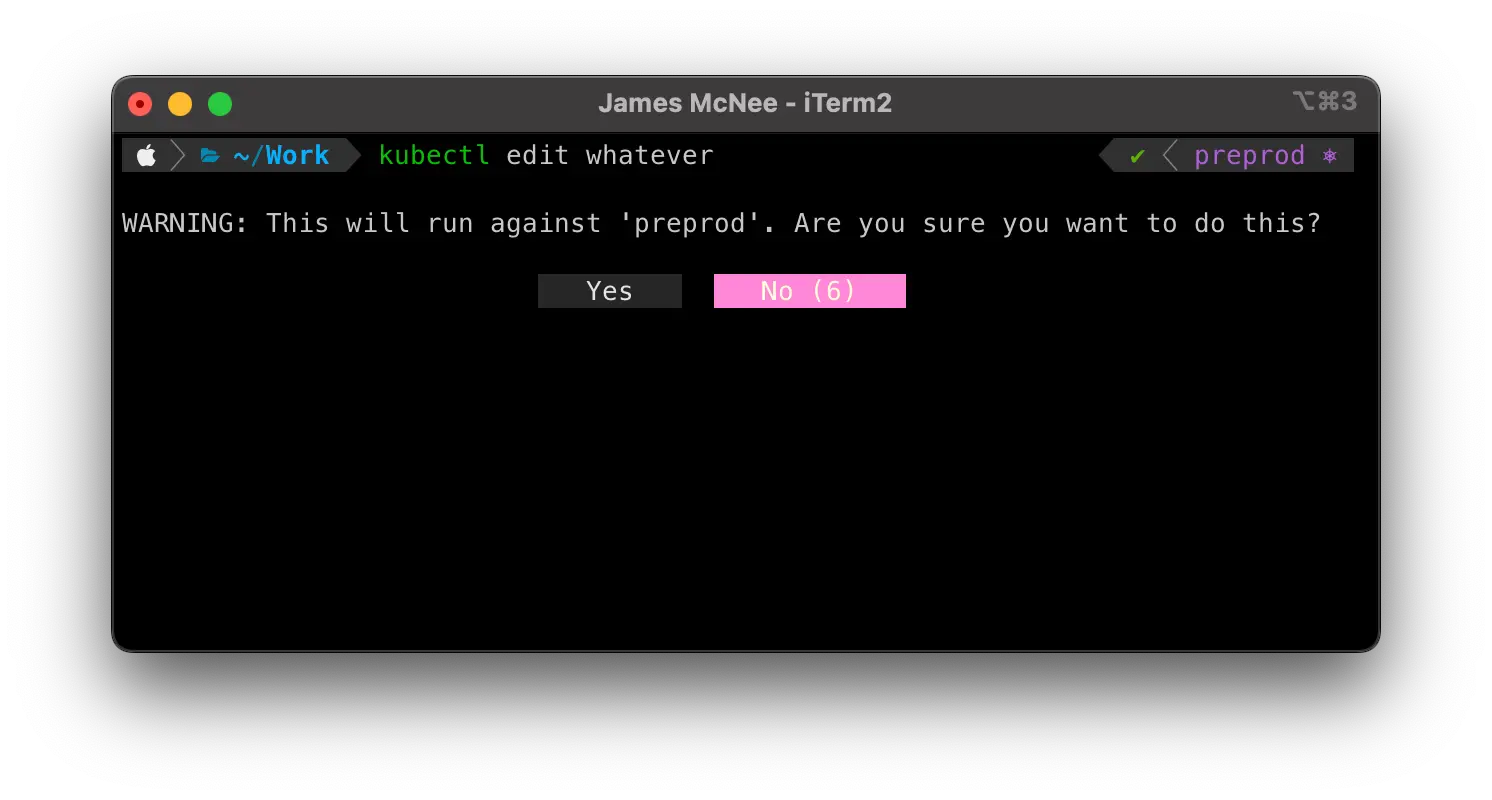

The first thing I needed to do was to create a wrapper script that I would invoke whenever I typed kubectl (or my alias k). I could then capture the command and perform the sniff test to see if it looks dubious. You can see what the result of this looks like in the screenshot above, just so you know what we are building.

I have a pattern for creating my shell scripts and an automated way of sharing dependencies between them, which I may write about at some point, but for now, I will keep it simple. I tend to have a main function to contain any logic, this is mainly for variable scoping, but it also aids with reading. First, I create two variables, one that will point at the real kubectl binary and another that will get the currently active kube context.

#!/bin/bash

function main() {

local KUBECTL_PATH="${HOME}/kubernetes/kubectl"

local CURRENT_CLUSTER=$(${KUBECTL_PATH} config current-context)

}

main "$@"Now, let's take an iterative approach. We will get something working quickly and then enhance it, so firstly let's just only allow actions to take place if the context is `testing'.

#!/bin/bash

function main() {

local KUBECTL_PATH="${HOME}/kubernetes/kubectl"

local CURRENT_CLUSTER=$(${KUBECTL_PATH} config current-context)

if [[ $CURRENT_CLUSTER != "testing" && -n $1 ]]; then

exit 1

fi

"${KUBECTL_PATH}" "$@"

}

main "$@"With the above, we are aborting if the current kube context is not testing and if it is, we continue, passing through the original arguments to the real kubectl binary.

Now, rather than just exiting early, let's make the script ask us to confirm if we intend to perform the action.

#!/bin/bash

function main() {

local KUBECTL_PATH="${HOME}/kubernetes/kubectl"

local CURRENT_CLUSTER=$(${KUBECTL_PATH} config current-context)

if [[ $CURRENT_CLUSTER != "testing" && -n $1 ]]; then

if ! gum confirm "WARNING: This will run against '${CURRENT_CLUSTER}'. Are you sure you want to do this?" --default="false" --timeout="10s"; then

echo "CANCELLED: Aborting command; that was close!" >&2

exit 1

fi

fi

"${KUBECTL_PATH}" "$@"

}

main "$@"Awesome, now, by using gum, we will be asked if we are sure that we wish to execute the command against a production cluster.

We could stop there, as this fulfils the objective that we set out with, but there are some operations that I don't need to be asked to confirm, even for production. Things like

- kubectl get when looking at cluster state

- kubectl logs when grabbing pod logs

- kubectl version when looking at what binary version I am running

So let's enhance the script to exclude those, and some more 'safe' commands. What you deem to be a safe command may differ, and that is fine, edit as appropriate.

#!/bin/bash

function main() {

local KUBECTL_PATH="${HOME}/kubernetes/kubectl"

local CURRENT_CLUSTER=$(${KUBECTL_PATH} config current-context)

local SAFE_OPERATIONS=(

"get"

"explain"

"describe"

"logs"

"completion"

"config"

"api-resources"

"version"

)

local SAFE_OPERATIONS_PIPE_DELIMITED=$(IFS="|"; echo "${SAFE_OPERATIONS[*]}")

if [[ $CURRENT_CLUSTER != "testing" && -n $1 ]]; then

if echo "$1" | grep -qvE "^(${SAFE_OPERATIONS_PIPE_DELIMITED})$"; then

if ! gum confirm "WARNING: This will run against '${CURRENT_CLUSTER}'. Are you sure you want to do this?" --default="false" --timeout="10s"; then

echo "CANCELLED: Aborting command; that was close!" >&2

exit 1

fi

fi

fi

"${KUBECTL_PATH}" "$@"

}

main "$@"Boom! Now we will only be asked to confirm potentially destructive actions (edit, delete, scale and apply etc).

Ensuring that the wrapper is invoked

Now, we have a script that wraps kubectl, but now we need to make sure that it actually gets invoked, not only when I type kubectl or use an alias, but also if any other application tries to, because I don't want that modifying production either!

To achieve this, I created another very small script and called it kubectl, which I then placed in a location which is referenced in my PATH. This script simply executes the shim we created above. This looks like the following

#!/bin/bash

/path/to/where/shim/is/located/kube-shim.sh "$@"I then created an alias for my preferred k invocation in my .zshrc file that invokes this shim script. Now, anything that attempts to use kubectl will be routed through the shim script. You could also if you wanted, just use the one script (i.e. place the shim in a bin folder and call it kubectl) but for my setup, I separated them.

Summary

To summarise, having a safety net around 'dangerous' operations on production infrastructure is blissful, obviously, even with mechanisms in place to prevent accidents from happening, complacency should be avoided.

Hopefully, this post will help you create a similar safety net around some of your binaries, or at least introduce you to gum, which is awesome.

Please feel free to share your thoughts and questions about this post!